Math is not so hard – keeping political promises is

The federal debt is so large that if the interest rate the government pays rose just 1 percentage point, the additional annual cost would be equivalent to the cost of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars combined.

By Antony Davies at Mercatus Center

At a campaign stop in New Hampshire last week, Mitt Romney promised that  he wouldn’t raise taxes on middle-income Americans. Like all politicians, Romney knows the three things voters want: no tax increases, no Social Security and Medicare cuts, and no deficits. The problem is that delivering all three is a mathematical impossibility.

he wouldn’t raise taxes on middle-income Americans. Like all politicians, Romney knows the three things voters want: no tax increases, no Social Security and Medicare cuts, and no deficits. The problem is that delivering all three is a mathematical impossibility.

To the astonishment of most economists, President Obama keeps saying that the rich need to pay “their fair share” of taxes. Forget the fact that, by leaving “fair” undefined, any tax rate, no matter how high, can be arbitrarily deemed “unfair.” Forget the fact that, according to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), the average American in the top 1 percent earns 20 times what the average American earns, yet pays 40 times the taxes.

The more pressing concern is that there aren’t enough rich people to tax to raise enough money to balance the budget.

Want to balance the budget on the backs of the top 1 percent? According to CBO figures, the government would need to tax them at a rate of almost 100 percent. But doing so would make the top 1 percent poor — so, next year, the government would have to tax the top 2 percent.

With the top 2 percent taxed into poverty, the year after that, politicians would need to go after the top 3 percent. Keep going down that path and, eventually, they’ll come for you.

This is where the middle class comes in. Politicians know the real potential for tax revenue lies with the middle class. Middle-income Americans far outnumber the rich and, at least for now, are taxed at relatively low rates. But even if we tapped the middle class, we’d have to raise tax rates by a staggering amount.

To balance the budget, we’d have to triple tax rates on every household earning over $100,000. Alternatively, we could merely double tax rates, but we’d have to do it on every household earning over $75,000. Not only are there not enough rich households to tax, there are barely enough middle-income households.

To balance the budget, we’d have to triple tax rates on every household earning over $100,000. Alternatively, we could merely double tax rates, but we’d have to do it on every household earning over $75,000. Not only are there not enough rich households to tax, there are barely enough middle-income households.

Conclusion: The only way to avoid raising taxes on the middle class is either to cut Social Security and Medicare or to live with persistent deficits.

But why not cut something else, like the Mars rover, or close some military bases, or freeze teacher salaries? Because these cuts are all meaningless.

NASA estimates that the annual cost of the Mars rover, Curiosity, is $325 million. Since the federal government spends at a rate of over $400 million per hour, scrapping Curiosity would save enough money to keep Washington chugging along for a grand total of 45 minutes.

Forget about mothballing an aircraft carrier here or closing a military base there. Shutting down the entire Department of Defense would only get us halfway to closing the deficit. To even come close to balancing the budget, we’d need to shut down the entire federal government with the exception of Social Security, Medicare and interest payments on the debt.

Conclusion: The only way to avoid cuts to Social Security and Medicare is to raise taxes on the middle class or to live with persistent deficits.

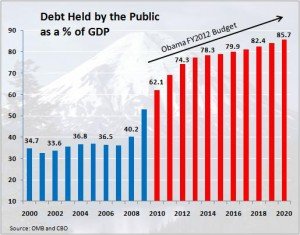

So what’s wrong with persistent deficits? The federal government, currently  $16 trillion in debt, will collect $2.5 trillion in taxes this year. That’s like shouldering a $320,000 debt on a $50,000 income. The federal debt is so large that if the interest rate the government pays rose just 1 percentage point, the additional annual cost would be equivalent to the cost of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars combined.

$16 trillion in debt, will collect $2.5 trillion in taxes this year. That’s like shouldering a $320,000 debt on a $50,000 income. The federal debt is so large that if the interest rate the government pays rose just 1 percentage point, the additional annual cost would be equivalent to the cost of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars combined.

This election, both candidates will promise some combination of no tax increases, no Social Security and Medicare cuts, and smaller deficits. Since you can only have two of the three, make sure to ask which they plan on not delivering.

Antony Davies is an associate professor of economics at Duquesne University. His primary research interests include forecasting and rational expectations, consumer behavior, international economics, and mathematical economics.

Help Make A Difference By Sharing These Articles On Facebook, Twitter And Elsewhere: