Two Attitudes Toward The State

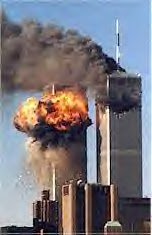

I have been involved in libertarianism or Objectivism since I was 15 years old but after 9/11, after seeing the ease with which a police state established itself, I wondered if I had wasted my life.

By Wendy McElroy at Whiskey & Gunpowder

[Address delivered at FreedomFest, Las Vegas, Nevada, July 14, 2012]

I expect the worst of the economic, the political turmoil we are all going to  have to deal with will hit in 2013 or, perhaps, the last months of this year. I expect the hard times to last for at least several years.

have to deal with will hit in 2013 or, perhaps, the last months of this year. I expect the hard times to last for at least several years.

Every morning I wake up and browse about 20 newspaper or media sites in order to stock the two daily newsfeeds I maintain. So I have no illusion about the condition of the world or about the immediate future. It is dismal.

And, yet, I’m an optimist.

I am an optimist about freedom…and not just the abstract concept but living freedom in my own time. It is not that I’m mentally deficient…and it is not because I haven’t been paying attention.

As bizarre as it may sound, my current attitude arose as a result of my turning 9/11 over and over in my mind. I gave a lot of thought to what my relationship to the state was and what it should be. Nothing has politically shocked as much as the 9/11 experience.

I call it an experience because, for me, 9/11 was far more than the terrorist acts that occurred on one day. For me, it was and is primarily America’s reaction in 9/11′s wake. The entire nation seemed to give up on freedom. America seemed almost eager to surrender every freedom on which it was built. And the police state came into being so fast.

To me, the symbol of 9/11 and the legacy it left America – or, rather, the  legacy America chose to embrace – can be seen at the airports where the Bill of Rights has been obliterated. Customers line up like criminals to permit uniformed agents of the state sexually assault them and their children, they allow their possessions to be pawed through. More than allow it…many people demand it in the name of security and then turn angrily on anyone who even raises the question of civil liberties.

legacy America chose to embrace – can be seen at the airports where the Bill of Rights has been obliterated. Customers line up like criminals to permit uniformed agents of the state sexually assault them and their children, they allow their possessions to be pawed through. More than allow it…many people demand it in the name of security and then turn angrily on anyone who even raises the question of civil liberties.

I have been involved in libertarianism or Objectivism since I was 15 years old but after 9/11, after seeing the ease with which a police state established itself, I wondered if I had wasted my life.

The title of my presentation this morning is “Two Attitudes Toward the State” and I want to explain two attitudes between which I’ve swung for many years and are still present within me today.

Before moving onto them, however, I should be clear that I am talking about attitudes and not my evaluation of the state, which remains unchanged. The state is a thug.

Basically, it relies upon two things to elicit cooperation from people in order to ‘convince’ them to surrender their rights and wealth.

The first is the myth of legitimacy; this is the notion that an electoral process or a hereditary line-of-succession or “fill in the blank” establishes an elite group who consist of politicians and those with political pull. These elite individuals somehow have the ‘right’ to tell other individuals what to say and what to do with their own body. They live by a double standard. Theft is wrong except if done by them in the form of taxation. Killing innocent people is wrong except if done by them in the war against terrorism.

Today the myth of legitimacy is being widely seen for what it is: a myth. Every day, fewer and fewer people believe in the legitimacy of the elites. And without that myth, their actions are being seen for what they are: a vicious double standard that excuses theft and murder. This means the state has to increasingly use the second method by which it elicits your cooperation: raw force or the threat thereof. And a sure sign that the elites have lost legitimacy and know it is the fact that they are becoming more violent toward their own citizenry by the hour.

So…I have no illusions about the condition of the world and my evaluation of the state has not changed.

I should return to attitudes. The first attitude toward the state that I want to examine was best expressed in a talk by David Friedman in which he assured the audience there was an Italian saying that translated into something like “It is raining again…PIG OF A GOVERNMENT!”

I remember wincing in my seat because I had a sudden vision of myself, standing in an open street, with my fist raised in fury at the political injustice of the drizzle hitting my face. The meaning of the saying, of course, is that many people blame everything on government. This hit too close to home. I was spending so much time railing against the State that I was running the risk of defining myself by what I oppose. I was taking the state inside myself and allowing it to filter my approach to life and determine many of my emotional reactions.

To some degree that process is inevitable. Sometimes the state seems to be everywhere. As long as you care about injustice, you’re going to react deeply at the sight of it. Frankly, that reaction is not something I intend to root out from within myself. I like it. Even if the reaction doesn’t always ‘feel’ good – sometimes it can feel almost sickening – it is something I prefer to the alternative of not caring.

Having said that, I also want a life in which I am not constantly reacting to injustice, constantly crying out against the state. I’ve seen too many good people burn out, I’ve seen them become bitter, or just lose their joy in living. And, so, after 9/11, I tried to find a balance in how I ‘consume’ the state…if you want to use an economic term. Or, in how I filter the state, if you want to use a psychological term.

An invaluable resource in that quest has been Henry David Thoreau’s essay “On Civil Disobedience.” Specifically, I turned over and over the story of his famous one-night stay in jail for refusing to pay a tax…and what happened directly after his release. And here I’ll let Thoreau speak for himself…

“It was formerly the custom in our village, when a poor debtor came out of jail, for his acquaintances to salute him, looking through their fingers, which were crossed to represent the jail window….My neighbors did not thus salute me, but first looked at me, and then at one another, as if I had returned from a long journey. I was put into jail as I was going to the shoemaker’s… When I was let out the next morning, I proceeded to finish my errand, and, having put on my mended shoe, joined a huckleberry party…” Thoreau journeyed off with a swarm of children who moved joyfully through the fields and forest. At one point, Thoreau paused and noted to himself, “in the midst of a huckleberry field, on one of our highest hills, two miles off, and then the State was nowhere to be seen.”

Upon his release from jail, Thoreau felt no rage toward his neighbors, no bitterness. He did not brood or rail against the injustice of his arrest. He shed everything but the insights he had gathered from the experience. And, then, he went about what he called “the business of living.” That is a wonderful phrase. The business of living.

When a tax collector knocked on his door and confronted him with the demand to pay up, Thoreau probably asked himself the same question I’ve been asking myself since 9/11. Namely, what is my relationship to the State? In answering, it is important to understand that Thoreau’s refusal to pay the tax was not the act of a determined political dissident; it wasn’t part of a pattern in his life through which he fought for the ideal of freedom. Thoreau refused to pay because he knew the specific tax would support the Mexican-American war, which he thought was immoral; rendering support to the war violated his sense of decency. In short, he did not want to cooperate with evil.

But unless and until the state literally knocked on his door, Thoreau was happy to go about the business of living as though the state did not exist. His insight while standing on a high hill is simple but profound: “and then the State was nowhere to be seen.” The essay “On Civil Disobedience” is sometimes titled “On the Duty of Civil Disobedience” and that is a mistake. Thoreau did not believe people had a duty to confront the state except when it sought to make you an accomplice in the oppression of others. Anyone who stands up against injustice when the state is not at their door but at someone else’s deserves applause. But they should not do so at the expense of their primary duty, which is to live as deeply and honestly as possible. The primary business of life is living.

It is far more difficult today than in Thoreau’s time to find places where the state cannot be seen. But, perhaps, this makes it more important for us all to try.

These are the two attitudes toward the state that define my relationship to it. On the one hand, I still shake my fist at the sky and shout PIG OF A GOVERNMENT! On the other hand, I aggressively try to expand the areas of my life about which I can say “Here there is no state.” These are areas like my home, family, friends, my community, writing, working…these are areas where the government does not define or in most cases even affect what I do or how I feel.

In a sense, and it is a simplistic sense, what these two opposing attitudes express is a distinction that is key to the entire structure of libertarianism: the distinction between state and society which is most often expressed in economic terms. The standard expression comes from Franz Oppenheimer’s book The State in which he contrasted what he called “the political means” with “the economic means” of acquiring wealth or power. The political means is the use of force – the State; the economic means is cooperation – Society. By using force the unproductive State feeds on the productivity of Society.

In a sense, and it is a simplistic sense, what these two opposing attitudes express is a distinction that is key to the entire structure of libertarianism: the distinction between state and society which is most often expressed in economic terms. The standard expression comes from Franz Oppenheimer’s book The State in which he contrasted what he called “the political means” with “the economic means” of acquiring wealth or power. The political means is the use of force – the State; the economic means is cooperation – Society. By using force the unproductive State feeds on the productivity of Society.

Instead of making an economic distinction, however, I am making a psychological one. The attitude “PIG OF A GOVERNMENT!” is who I am in relationship to the State; that is my reaction when it knocks on my door and on the door of others. That reaction remains within me and I’ll be expressing it for as long as the State keeps knocking.

The attitude “here, there is no State” is who I am in relationship to Society as I go about the business of living. It involves a commitment. As much as possible I don’t use the services or so-called ‘benefits’ the government offers but seek private means instead. I explore alternative currencies and means of exchange like barter. I join networks of individuals who cooperate together for mutual benefits. In short, I am taking my life back from the state and privatizing it.

Oddly enough, the attitude of ignoring or obviating the State – again, as much as possible – may well be the most effective strategy for countering it. That’s not my purpose; my purpose is the business of living. But by privatizing your own life, you make the state increasingly irrelevant, which is what politicians fear most. They are desperate to be part of our lives, to teach our children, to regulate our work, to read our messages and hear our phone calls, to dictate our medical choices… And the most effective personal response when the State knocks at your door may well be to not answer even by the act of raising your fist.

Regards,

Wendy McElroy

Wendy McElroy is Author, lecturer, and freelance writer, and a senior associate of the Laissez Faire Club.

You can support her work by reading her special message about the Club and then joining. For list of books, documentaries, and other publications, please click here.

Help Make A Difference By Sharing These Articles On Facebook, Twitter And Elsewhere: